Eva Kanso and her team at the University of Southern California’s Viterbi School of Engineering have unlocked the secret of how brainless sea stars coordinate hundreds of tube feet. Their research, published in PNAS, reveals a decentralized control system that could revolutionize robotics, enabling autonomous machines to navigate upside-down, underwater, or on distant planets without a central processor.

How do you solve a complex navigation problem without a central command center? You could ask a sea star. These iconic marine animals perform a minor miracle daily, coordinating hundreds of tiny, independent tube feet to glide across complex surfaces—all without a brain to direct the operation. This mesmerizing puzzle caught the attention of Professor Eva Kanso and her Kanso Bioinspired Motion Lab at the USC Viterbi Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering. Their investigation into this “brainless” locomotion is now providing a radical new blueprint for building tougher, more adaptive robots.

The core problem this product—a bio-inspired decentralized control system—aims to solve is fragility. Traditional robots rely on a central computer or constant communication with an operator. If that link fails or the environment is too unpredictable, the system breaks. Sea stars, however, demonstrate incredible robustness through a distributed network. “We hypothesized that sea stars rely on a hierarchical and distributed control strategy, in which each tube foot makes local decisions,” said Eva Kanso.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/battery-made-from-rust-show-high-energy/

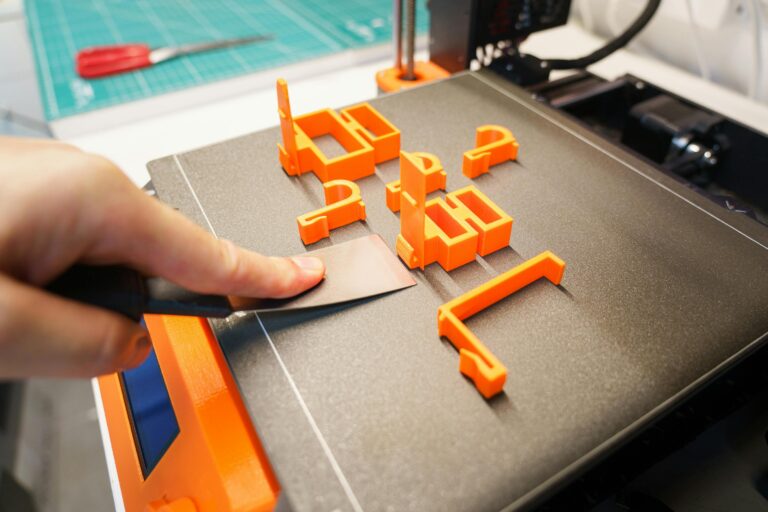

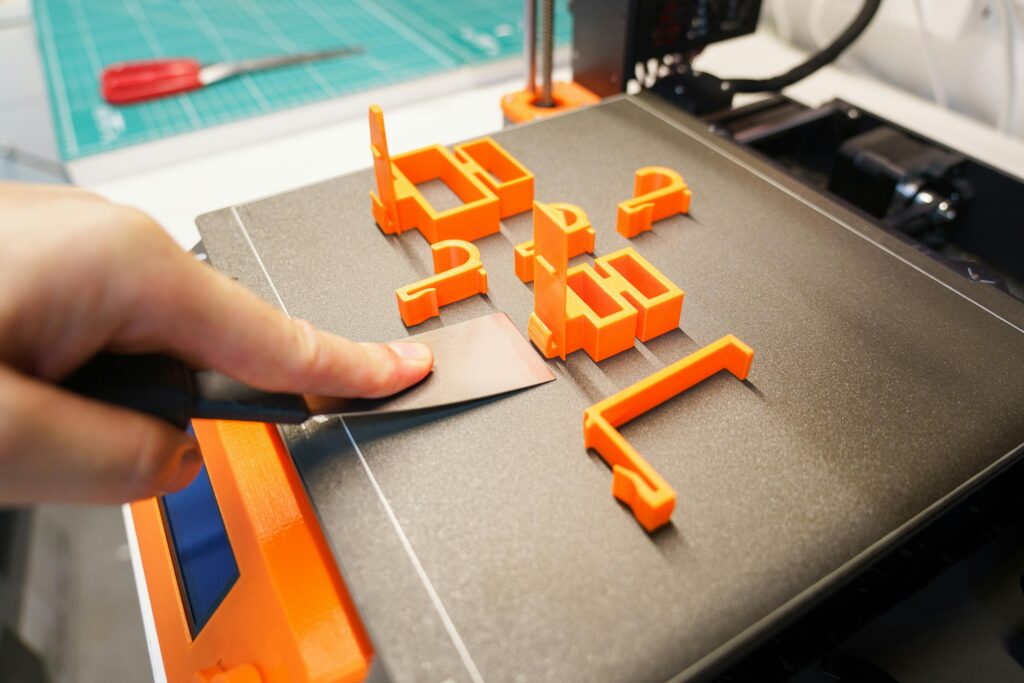

To test this, the team collaborated with biologists at the University of Mons in Belgium and the McHenry Lab at UC Irvine. They designed a clever experiment, fitting a sea star with a 3D-printed “backpack” to vary the load it carried. By watching how each tube foot responded, they confirmed a simple yet powerful principle. The basic function of the system is that each individual foot senses local mechanical strain and independently decides when to grip or release the surface, creating coordinated movement through the physical coupling of the body itself. It’s a lesson in simplicity: local sensing drives global action.

This approach has a profound limitation, albeit one that defines its niche. This decentralized, mechanical feedback loop is ideal for slow, deliberate, and highly adaptive movement but is not designed for the high-speed, precisely timed motions seen in animals with central nervous systems. A sea star won’t win a sprint, but it will almost never be truly stuck. As Kanso notes, “Just imagine if you were doing a handstand. Your nervous system would immediately let you know… But a sea star has no such collective recognition.” Its system doesn’t need to recognize the overall situation; each foot simply reacts to what it feels.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/china-largest-offshore-solar-project/

The overall summary and value of this research lies in its promise for resilient autonomy. Robots equipped with such a decentralized control strategy could navigate disaster zones, underwater pipelines, or the rugged terrain of other planets where maintaining a communication link is impossible. The system’s beauty is its redundancy. If one foot—or one robot module—fails, the collective effort continues. This makes it perfect for so-called soft robotics and machines that operate in extreme environments.

The path from marine biology to advanced robotics was forged by a clear division of creative roles. The innovator behind the core hypothesis and project vision is Professor Eva Kanso, while the engineering and experimental work was carried out by Associate Professor Sylvain Gabriele and graduate student Amandine Deridoux at the University of Mons’s SYMBIOSE Lab. This cross-disciplinary partnership was essential to translate a biological phenomenon into a quantifiable mathematical model and a tangible engineering principle.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/jaguar-electric-gt-frozen-lake-test/

Reported in their PNAS paper, the team’s mathematical model shows how simple local rules, mediated by body mechanics, produce complex locomotion. It’s a powerful lesson from nature: sometimes, the key to resilience isn’t a smarter brain, but a better-connected body. As the field of robotics pushes into ever more challenging frontiers, the humble sea star offers a timeless piece of engineering wisdom.