US Department of Energy scientists have taken a dramatic step toward solving one of climate science’s most stubborn mysteries, i.e., how clouds behave.

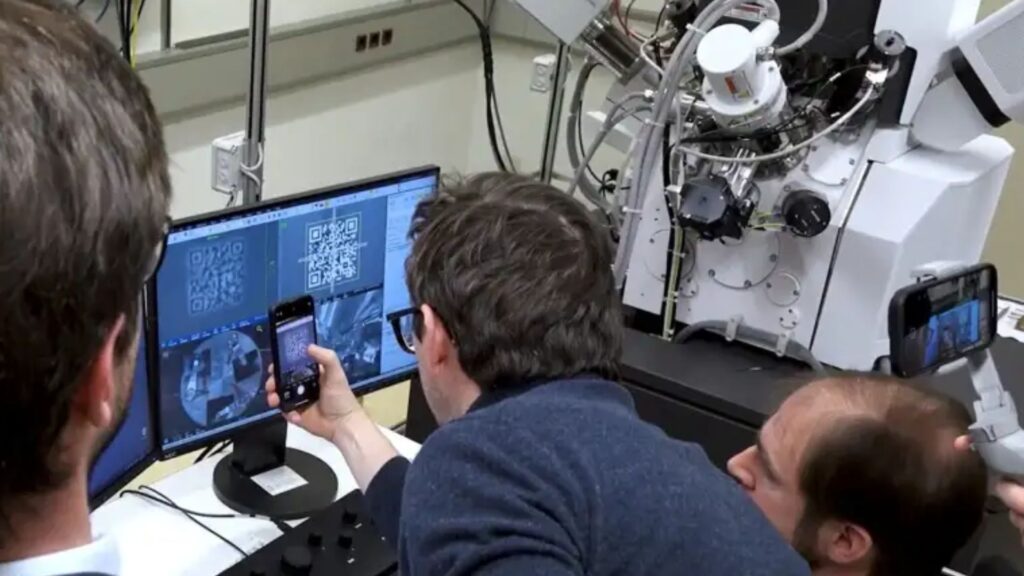

Inside a quiet lab at Brookhaven National Laboratory, researchers recently witnessed something both ordinary and extraordinary: the birth of a cloud.

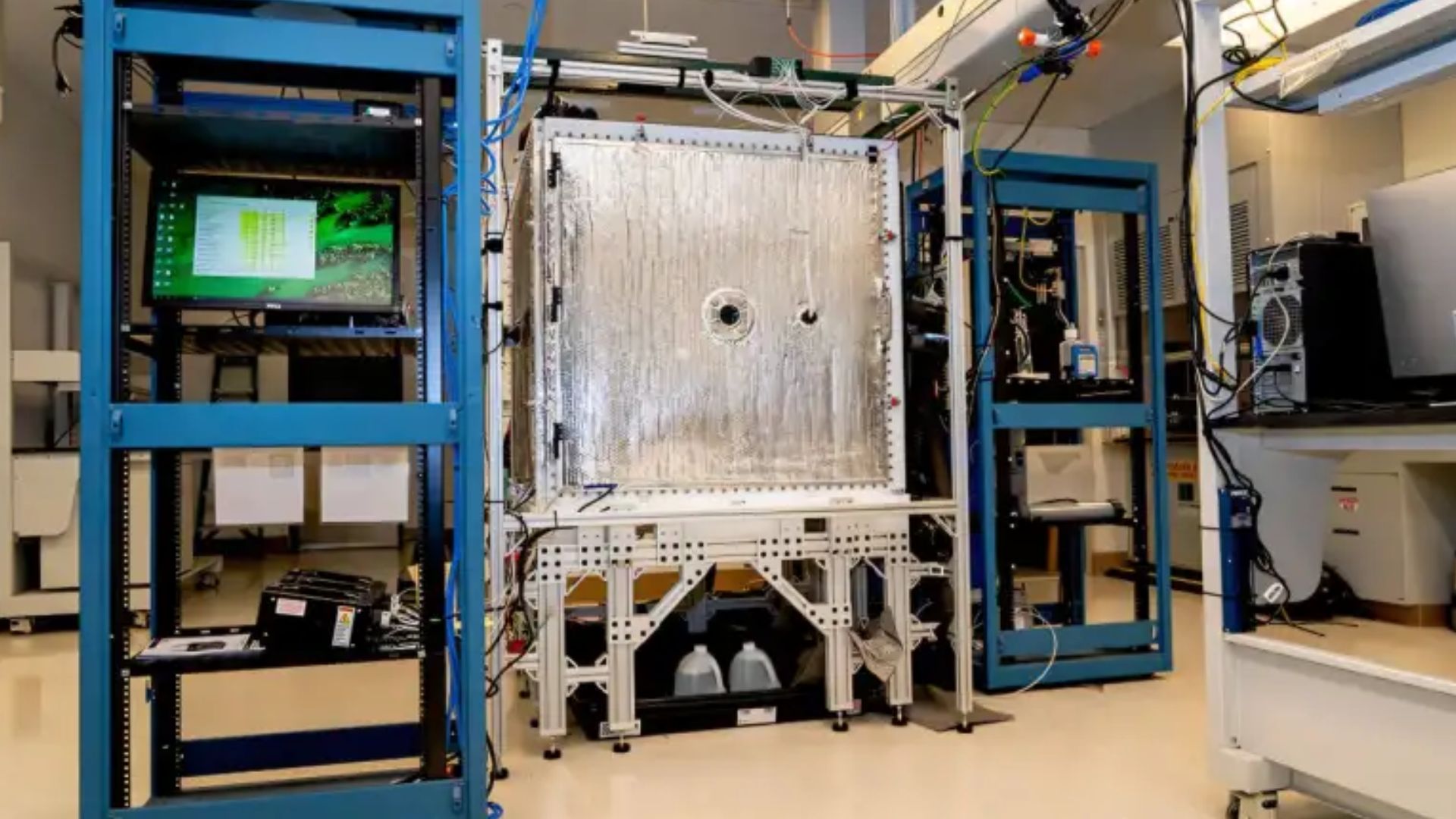

But this wasn’t drifting across the sky. It formed inside a one-cubic-meter steel chamber, a programmable atmosphere designed from scratch.

The system, called a “Cloud in a Box,” could redefine how scientists understand rainfall, storm intensity, and climate prediction.

Under a sheet of green laser light, tiny floating particles began to swirl. Within seconds, a faint haze thickened into a visible wisp of cloud. For the scientists gathered around, it was more than a visual triumph. It was a scientific milestone.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/3d-printer-filament-turns-into-robot/

“We saw the birth of a cloud,” said Brookhaven atmospheric scientist Arthur Sedlacek. “We felt excitement, happiness, and relief all at once. Needless to say, we weren’t quiet after that.”

The new convection cloud chamber, one of only two of its kind in the US, now allows scientists to create, sustain, and analyze clouds in fully controlled laboratory conditions.

Until now, researchers mostly depended on field studies, flying aircraft directly into clouds to collect fleeting measurements.

But clouds change rapidly. By the time an aircraft makes a second pass, the cloud has already evolved. This chamber changes that.

Clouds Climate Mystery

Clouds may look soft and simple from the ground. They are one of the largest sources of uncertainty in climate models.

They regulate Earth’s energy balance by reflecting sunlight and trapping heat. They drive storm formation and influence the intensity of hurricanes and other weather systems. But the precise microphysics inside clouds, including how droplets form, grow, and turn into drizzle, remains poorly understood.

“One long-standing unsolved problem in our community is how drizzle forms in warm clouds,” Sedlacek explained. “Why do some clouds produce rain while others don’t? We need controlled, repeatable experiments to isolate the factors responsible.”

That is exactly what the Brookhaven Chamber enables.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/biohybrid-robots-turn-food-waste-into-functional-machines/

How ‘Cloud in Box’ Works?

The chamber recreates the essential ingredients of cloud formation, such as supersaturated air and aerosol particles.

First, researchers fill the bottom baseplate with water and heat it. Water vapor rises upward. Meanwhile, the top panel remains chilled. As warm, moist air mixes with cooler air above, humidity levels climb beyond 100 percent, a state known as supersaturation.

“Cloud formation requires relative humidity greater than 100 percent,” Sedlacek said. “We achieve supersaturation by mixing warm humid air with cold humid air.”

But water vapor alone isn’t enough. Real clouds need tiny particles called aerosols to act as seeds.

Scientists inject microscopic particles such as salt into the chamber. Water vapor condenses onto these particles, forming cloud droplets. Over time, the droplets grow until the system reaches a steady balance between droplet size and humidity.

“One major advantage of a convection cloud chamber is that we can maintain a turbulent cloud for hours in a steady state,” said atmospheric scientist Fan Yang. “That allows us to repeat measurements and improve statistical accuracy.”

Unlike traditional cloud chambers, Brookhaven’s system includes adjustable heating and cooling panels along its sides. Researchers can fine-tune temperature gradients, turbulence, and humidity levels to dial in different types of cloud environments.

A central challenge in studying clouds is measurement itself. Inserting instruments directly into a cloud disrupts its structure and airflow. The Brookhaven team is solving this by using advanced light-based technologies.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/china-2d-semiconductor-wafer-production/

“We want to detect the transition from aerosols to droplets to drizzle without physically disturbing the cloud,” Sedlacek said. “To do that, we’ll use light.”

Scientists tag aerosol particles with fluorescent dye. When struck by a laser, activated particles glow, allowing researchers to track their transformation into droplets.

The team will also deploy time-correlated photon-counting lidar. It is a highly precise laser-based remote sensing system capable of observing cloud structures at centimeter-scale resolution. To monitor drizzle formation, they plan to use cutting-edge terahertz radar that can detect individual droplets and measure their fall speeds.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is also on the horizon. Researchers envision automated systems that adjust chamber conditions in real time to simulate complex atmospheric behavior.

“There are lots of knobs we can turn inside this chamber,” Sedlacek said. “We’re already thinking about incorporating AI into its workflow.”

The chamber’s creation reflects years of interdisciplinary collaboration between engineers, atmospheric scientists, and technical staff at Brookhaven.

Mechanical engineer Nathaniel Speece-Moyer described the design process as iterative and precise. “We weighed different options constantly while working closely with scientists to meet strict temperature-control requirements,” he said.

The modular design ensures all hardware remains outside the chamber, preventing interference with internal airflow. Many components were fabricated in-house, reducing costs and enabling design flexibility.

The project also drew inspiration from the Pi Cloud Chamber at Michigan Technological University, the only other convection cloud chamber in the country. Professor Raymond Shaw, who holds a joint appointment at Brookhaven, played a key role in developing both facilities.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/chinese-company-s-humanoid-robot-dodges-arrow-with-side-flip/

“Cloud chamber science is experiencing a resurgence,” Shaw said. “We still face fundamental questions about aerosol-cloud interactions that directly affect how we simulate storms and atmospheric flows.”

He added that advances in computational modeling now allow researchers to compare lab experiments directly with high-resolution simulations—something that wasn’t feasible a decade ago.

The region is often described as Earth’s deepest “gravity hole.”

Weather Forecasting

While its immediate focus is cloud microphysics, the chamber’s potential stretches far beyond meteorology.

Researchers are exploring how atmospheric conditions influence energy systems and communications infrastructure. The chamber could also shed light on how bioaerosols—such as pollen or pathogens—move through humid air.

“The environment we create inside this chamber opens doors to many applications,” Sedlacek said. “We welcome out-of-the-box ideas for how this capability can serve broader research.”

The chamber’s modular design even allows expansion. Adding another cubic meter could extend cloud lifetimes, enabling deeper study of raindrop formation and precipitation cycles.

As extreme weather intensifies worldwide and climate models struggle with uncertainties related to clouds, controlled laboratory experiments may hold the key to clearer forecasts.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/sodium-sulfur-battery-us-power-grid/

By isolating variables in a stable, repeatable environment, scientists can finally observe processes that were previously too chaotic to measure precisely.

Inside that steel cube at Brookhaven, researchers aren’t just making clouds but also reshaping how we understand the atmosphere itself.