Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) have harnessed supercomputing power to simulate one million unique orbits in the critical region between Earth and the Moon. Led by scientists Travis Yeager and Denvir Higgins, the massive, open-source dataset solves a fundamental navigation problem in cislunar space, providing a free blueprint for future missions and space traffic management in an increasingly crowded celestial neighborhood.

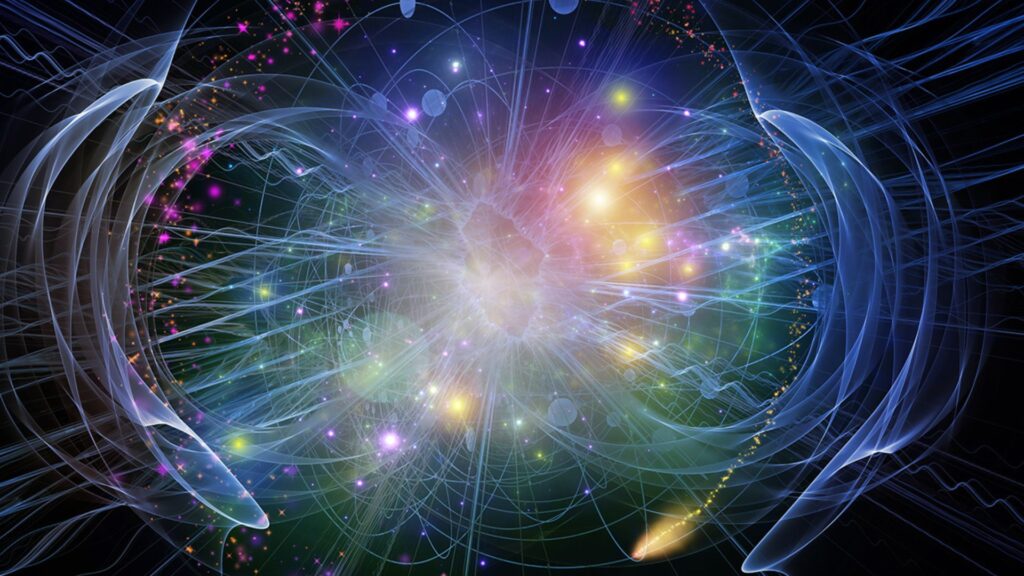

Figuring out where to safely park a satellite between Earth and the Moon isn’t like finding a spot in a grocery store lot. It’s more like predicting the path of a leaf in a hurricane, where the gravitational pull of multiple massive bodies creates a dynamic and chaotic highway. This is the immense challenge of cislunar space, the expansive zone encompassing orbits around Earth, journeys to the Moon, and the strategic points just beyond. The product of this research—a massive, open database of one million simulated orbits—solves the critical problem of predicting long-term stability in this complex environment, where a single miscalculation can lead to a lost multi-billion dollar asset.

So, how did they chart this celestial map? The basic function of their work is a sophisticated simulation tool that takes a spacecraft’s starting point and velocity, then uses physics to calculate its path forward in tiny, discrete steps over six-year lifetimes. This isn’t simple math. As LLNL scientist Travis Yeager explains, “If you want to know where a satellite is in a week, there’s no equation that can actually tell you where it’s going to be. You have to step forward a little bit at a time.” Their Space Situational Awareness Python package treats it as a high-fidelity N-body problem, accounting for the gravity of Earth, the Moon, and the Sun, plus subtle radiative forces.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/human-embryo-invasion-china/

The team made a conscious effort to avoid assumptions. “We tried to go into it pretending we knew nothing about this space,” Yeager said. They fed the simulation a vast range of starting conditions for orbits. Crucially, they moved beyond treating planets as simple points in space. “The Earth is not a point source. It is actually blobby,” Yeager notes, highlighting that accounting for our planet’s uneven mass distribution—a detail that makes modern GPS possible—was essential for accuracy in cislunar space.

This precision came at a staggering computational cost. Generating the full dataset required 1.6 million CPU hours, a task that would take a single computer over 182 years. Herein lies a key limitation of such high-fidelity modeling: the sheer resource intensity. Without access to world-class supercomputing, this project would be impossible. The team overcame this by leveraging LLNL’s Quartz and Ruby supercomputers and, importantly, by writing uniquely efficient code. “The interesting thing about our code is that it is parallelizable, whereas other commercial codes are not. We can spread jobs across nodes,” said co-author and LLNL scientist Denvir Higgins. This allowed them to complete the million-orbit simulations in just three days.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/china-6-ton-tiltrotor-first-flight/

The results are a treasure trove for the future of space operations. Of the million orbits simulated, 54% remained stable for at least one year and 9.7% for the full six years. But even the unstable trajectories hold immense value. The overall summary and value of this project is that it provides an unprecedented, public foundation for mission planning, space traffic coordination, and scientific discovery, reducing risk and cost for all spacefaring nations and entities. Higgins points to the data-science potential: “When you have a million orbits, you can get a really rich analysis using machine learning applications… try to predict stability or try to do anomaly detection.”

This work paves the way for smarter space infrastructure. By analyzing this data, researchers can identify the cosmic equivalent of “busiest intersections,” ideal locations for sentinel satellites to monitor traffic. This is increasingly vital as launches proceed without global coordination. The innovator behind the project’s conceptual approach was scientist Travis Yeager, while the engineering feat of building the parallelizable code and executing the simulations was led by Denvir Higgins and the LLNL computational team. Their collaborative effort transformed a theoretical challenge into a practical, shared resource.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/worlds-fastest-falcon-seen-in-australia/

Reported by LLNL, the team has made both the database and the underlying code publicly available, inviting the global community to build upon their work. Funded by a Laboratory Directed Research and Development project, this initiative isn’t just about data—it’s about fostering open collaboration in the next frontier. As cislunar space becomes the focus of 21st-century exploration, this million-orbit map is the essential guidebook we didn’t know we needed.