Peking University researchers have discovered that Earth’s metallic core may contain nine to forty-five times the volume of hydrogen found in all the planet’s oceans combined. Led by Dr. Dongyang Huang, Assistant Professor in the School of Earth and Space Sciences, the team used atomic-scale imaging to estimate that hydrogen makes up roughly 0.07% to 0.36% of the core’s total weight—suggesting Earth was born with most of its water, not showered by comets later.

The problem Dr. Huang and his colleagues set out to solve is one of the oldest in planetary science: where did Earth’s water actually come from? For decades, textbooks favored the comet delivery hypothesis—icy impactors bringing water to a dry planet. But that theory always carried an uncomfortable implication. If comets delivered surface water, why does Earth’s deep interior still hold so much hydrogen that it defies measurement?

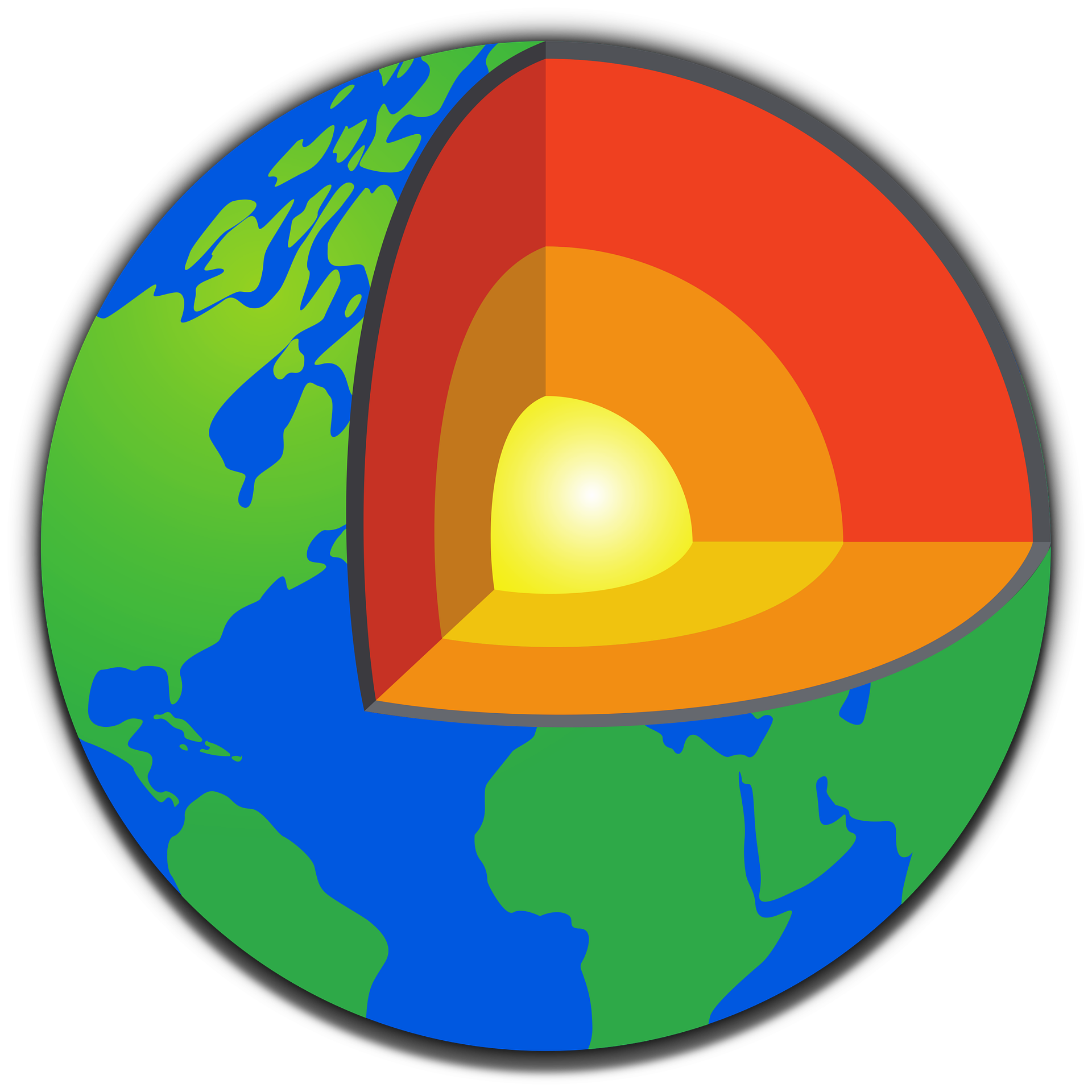

What the team built, in essence, was a window into the planet’s basement. Using a technique called atom probe tomography, the researchers vaporized needle-thin iron samples—20 nanometers wide—inside a diamond anvil cell while firing lasers to replicate the immense pressures and temperatures of Earth’s core. The device then counted individual atoms as they ionized. For the first time, scientists could directly observe how hydrogen bonded with silicon and iron under conditions that mimic 4.6 billion years of planetary isolation.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/chinese-surgeons-ear-grafted-to-foot/

The basic function of this method is straightforward in concept, fiendishly difficult in execution. It tells geophysicists what ratio of hydrogen to silicon freezes into metal as liquid iron cools. Dr. Huang’s team found that ratio hovers near one-to-one. Combined with existing estimates of core silicon, that simple proportion opens a calculation that has eluded the field for generations.

Still, the work carries an honest limitation that the researchers themselves emphasize. Hydrogen is the lightest element and the most slippery to measure. Some of it inevitably escaped from the iron samples as pressure was released inside the laboratory, a documented loss that the current calculations do not fully capture. According to Kei Hirose, a professor at the University of Tokyo’s School of Science who was not involved in the study, the core’s actual hydrogen content could be even higher—potentially 0.2% to 0.6% by weight, a range that would push the estimate toward the upper bound of forty-five oceans.

What makes this matter, ultimately, is not the sheer tonnage of hydrogen locked 1,800 miles beneath our feet. It is what that reservoir implies about how planets become habitable. Hydrogen is one of six essential elements for life, according to Rajdeep Dasgupta, a professor of Earth systems science at Rice University in Texas, who called hydrogen indispensable alongside carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus. If the core sequestered most of the planet’s hydrogen within the first million years of accretion, then the conditions for life were set before the crust even solidified.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/isro-gaganyaan-crew-parachute-validation/

The innovator of this atomic-scale approach is Dr. Dongyang Huang, who trained as an experimental petrologist before joining Peking University. But the engineers who made the measurements possible—the team of laboratory scientists at Peking University’s high-pressure geochemistry facility—spent years refining the atom probe tomography protocols that allowed them to count hydrogen atoms one by one. It is one thing to theorize about deep Earth volatiles. It is another to build the apparatus that sees them.

Reported by CNN, the study published in Nature Communications on Tuesday represents a technical leap over earlier X-ray diffraction methods, which inferred hydrogen presence indirectly by measuring how much iron crystals expanded. Those interpretations varied so wildly—from 0.1 oceans to more than 120 oceans—that they offered little constraint. The new atomic counts narrow that range by a factor of ten.

What remains unresolved, and what the authors acknowledge with careful scientific restraint, is whether this hydrogen originated from primordial nebular gas, from water-bearing asteroids, or from some combination that played out during Earth’s main growth phases. Dr. Huang told CNN that the core stored most of its water in the first million years. Professor Hirose notes that comets and asteroids likely contributed as well. The two positions are not mutually exclusive, but they tilt the intellectual weight back toward an older idea: that Earth was born wet, not watered later.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/nasa-targets-500kw-nuclear-reactor-moon/

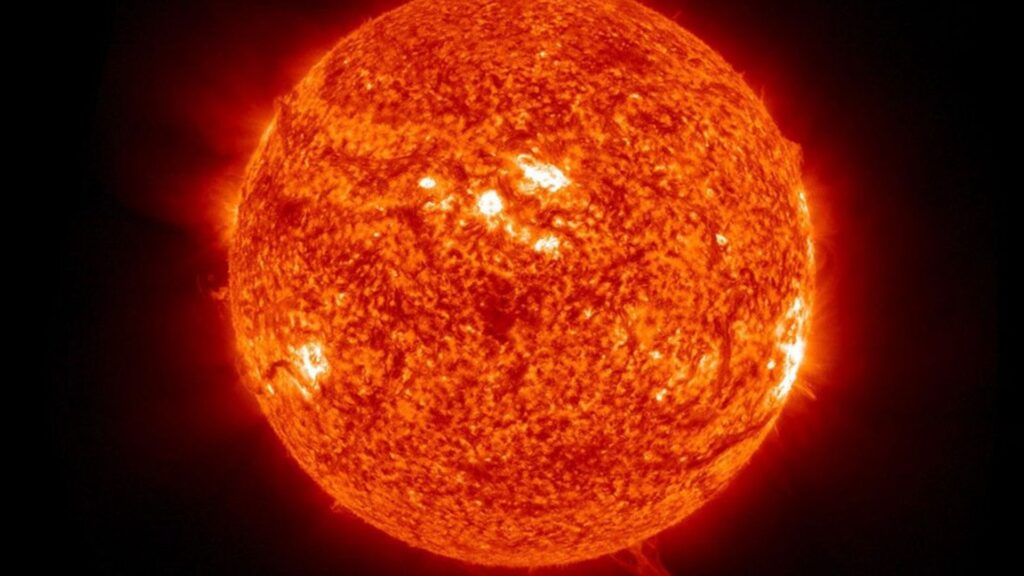

For the rest of us, standing on crust that contains the least hydrogen of any terrestrial layer, the discovery reframes what we mean when we call Earth the Blue Planet. The oceans we see are merely the condensation on a much deeper reservoir. Somewhere beneath the mantle, circulating in liquid metal at temperatures exceeding those on the sun’s surface, there may be nine Earths’ worth of hydrogen we never knew existed.