Researchers from ETH Zurich have identified a narrow chemical “Goldilocks zone” during planetary formation that dictates whether worlds retain enough phosphorus and nitrogen—two elements essential for life. Their models show Earth’s oxygen levels during core formation 4.6 billion years ago were precisely balanced, a rare cosmic stroke of luck that may drastically narrow the search for habitable exoplanets.

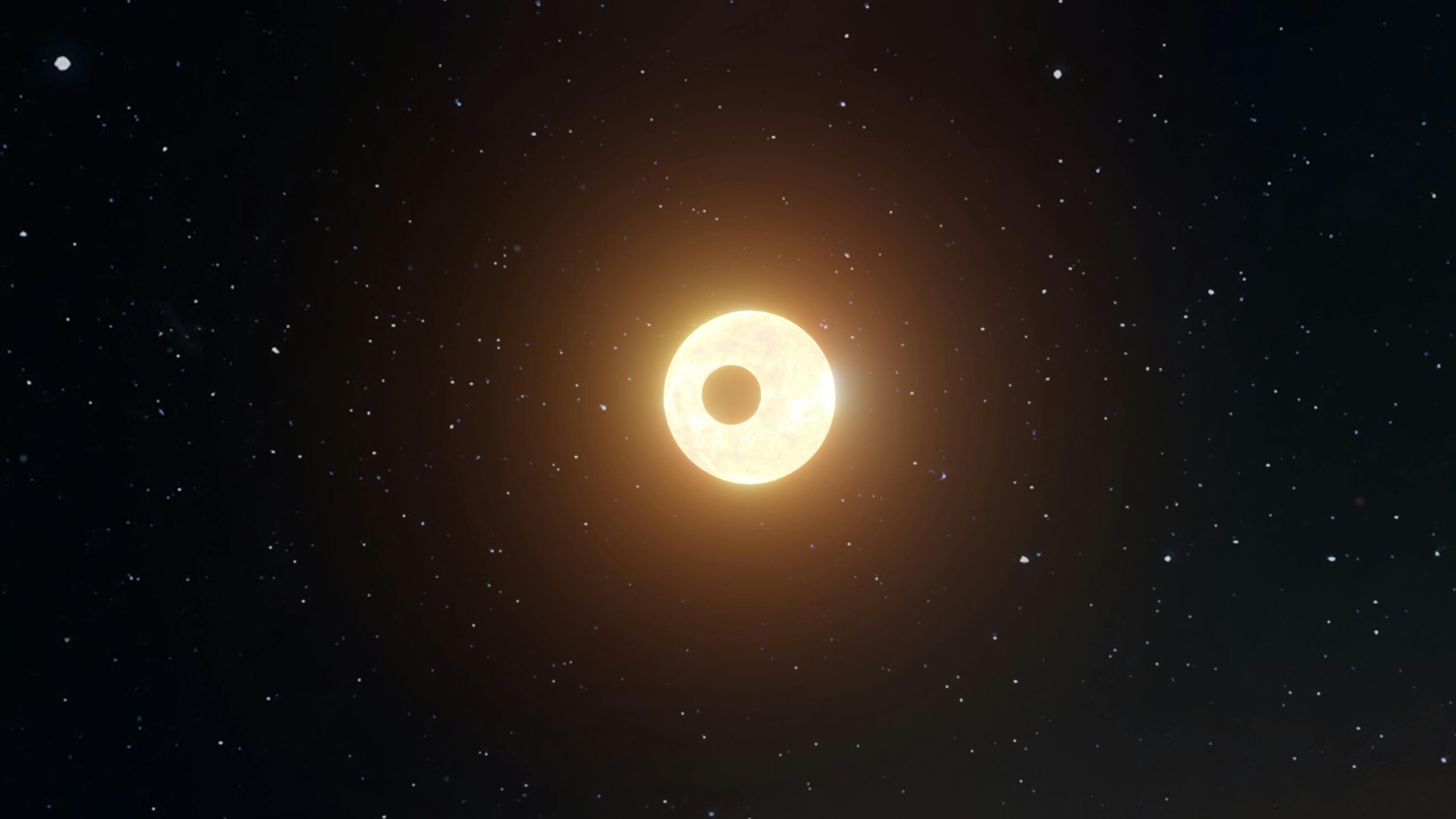

We often picture the search for alien life as a hunt for Earth-like planets—worlds with water, a stable atmosphere, and the right temperature. But what if the most important filter for life isn’t found on the surface, but was locked in during a planet’s violent, molten birth? New research suggests that the very chemistry that makes life possible might be a cosmic rarity, determined in the first moments of a planet’s existence.

A team at ETH Zurich’s Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life has turned planetary science on its head by focusing on two humble elements: phosphorus and nitrogen. You won’t find them making headlines like water or oxygen, but without them, life as we know it is impossible. Phosphorus forms the backbone of DNA and RNA and is crucial for cellular energy. Nitrogen is a fundamental building block of proteins. The question is: why does Earth have just the right amount, while other rocky planets seem to miss the mark?

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/how-diesel-submarines-work-underwater/

This research tackles a profound mystery in astrobiology: why, even if a planet is in the habitable “Goldilocks zone” of its star, it may still be utterly sterile due to a lack of life’s essential chemical ingredients.

The study reveals that the availability of these elements isn’t about what happens later on a planet’s surface, but about a one-time, irreversible chemical sorting that occurs as the planet forms from a magma ocean. As heavy metals like iron sink to form the core, the amount of oxygen present acts as a cosmic referee, deciding the fate of phosphorus and nitrogen.

The research was led by postdoctoral researcher Craig Walton and ETH professor Maria Schönbächler. Through extensive geochemical modeling, their team engineered virtual planetary formations to trace the journey of these critical elements under varying conditions. “During the formation of a planet’s core, there needs to be exactly the right amount of oxygen present,” explains Craig Walton, the study’s lead author.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/china-massive-tank-live-fire-test/

Here’s the delicate cosmic balance: if there’s too little oxygen during core formation, phosphorus bonds with iron and gets dragged into the planet’s deep core, lost forever to the surface. If there’s too much oxygen, phosphorus stays in the mantle, but nitrogen becomes volatile and escapes into space. Life needs both.

The study identifies a key constraint: the “chemical Goldilocks zone” of oxygen is exceptionally narrow. Only planets that form within this precise window end up with sufficient phosphorus and nitrogen in their mantle and crust to later seed biology. It’s a lottery most planets seem to lose.

The overarching value of this finding is a new, more stringent framework for the search for extraterrestrial life. It moves the goalposts from simply looking for planets with water to evaluating the fundamental stellar and planetary chemistry that predates surface conditions. It suggests life may be chemically impossible on far more worlds than we previously assumed.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/porsche-cayenne-electric-production-starts/

The models show Earth hit the jackpot. “If we had had just a little more or a little less oxygen during core formation, there would not have been enough phosphorus or nitrogen for the development of life,” says Walton. In contrast, planets like Mars formed outside this zone, resulting in a mantle richer in phosphorus but critically depleted in nitrogen—a challenging cocktail for life.

This reframes our search strategy. Since a star’s chemical composition dictates the material available to its planets, astronomers should prioritize studying solar systems with stars similar to our Sun. “We should look for solar systems with stars that resemble our own Sun,” Walton advises. Solar systems with starkly different chemistries might be dead from the start.

The ETH Zurich work, published in a leading planetary science journal, is a humbling reminder of our planet’s profound good fortune. It wasn’t just being in the right place orbitally; it was being born with the right chemical recipe at the right time. As we scan the galaxy, we may not just be looking for another Earth. We may be looking for another cosmic miracle.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/byd-seal-smooth-electric-power/