Researchers from Northwestern University have decoded the precise chemistry that allows common iron oxide minerals in soil to trap and store vast amounts of carbon. By studying ferrihydrite, the team discovered it uses a nanoscale mosaic of mixed charges plus multiple bonding strategies—not just simple attraction—to lock away diverse organic molecules for decades or centuries.

Soil is Earth’s silent climate ally, holding a staggering 2,500 billion tons of sequestered carbon. But how does it keep that carbon locked away? While iron oxides have long been recognized as key players, the exact mechanisms remained murky. A new study led by Professor Ludmilla Aristilde at Northwestern University provides the most detailed answer yet, revealing a surprisingly versatile and multi-talented carbon trap operating at the molecular level.

The research, published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, zeroed in on a mineral called ferrihydrite. Common in soils near plant roots, it’s associated with more than one-third of the organic carbon stored globally. The prevailing assumption was simple: because ferrihydrite typically carries an overall positive charge, it should only attract negatively charged molecules. But nature, as it turns out, is far more clever.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/us-most-radioactive-site-post-manhattan-project/

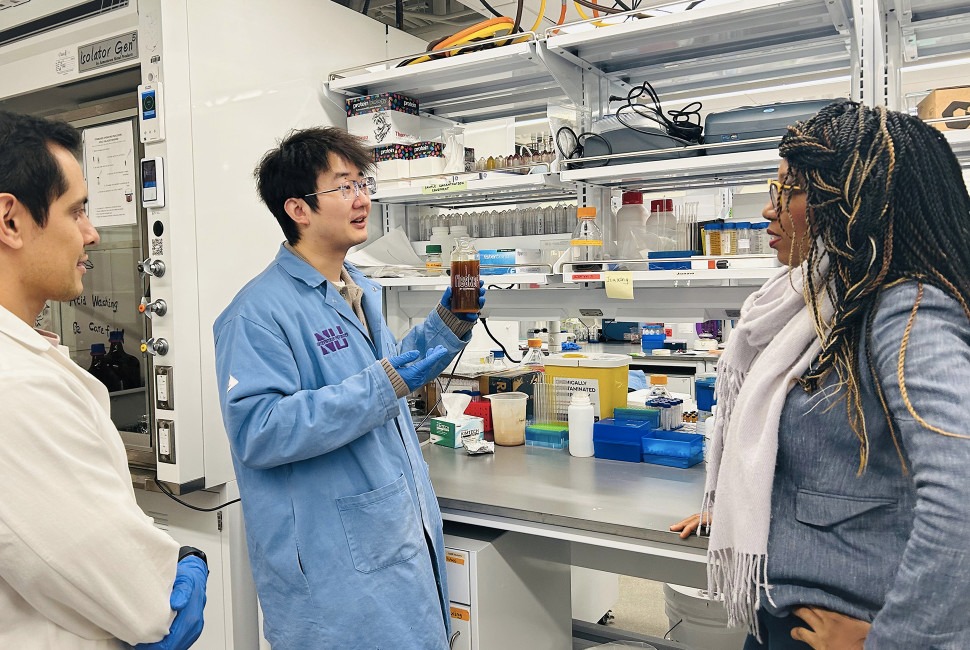

Using high-resolution molecular modeling and atomic force microscopy, the team mapped the mineral’s surface with unprecedented detail. What they found was a game-changer. “It is the sum of both negative and positive charges distributed across the surface that gives the mineral its overall positive charge,” explained Professor Aristilde, an expert in environmental organics dynamics. The surface isn’t a uniform sheet of charge; it’s a nanoscale mosaic of intermixed positive and negative patches. This intricate landscape immediately explained how the mineral can interact with a wide range of compounds, reported Northwestern University.

But the surprises didn’t end there. The team then introduced various soil-derived organic molecules—like amino acids, sugars, and plant acids—to the ferrihydrite. By measuring what stuck and using infrared spectroscopy to see how it stuck, they uncovered a versatile chemical toolkit. Positively charged amino acids bonded to negative patches, while negatively charged ones found positive patches. Other molecules, like ribonucleotides, were first drawn in by electrostatic attraction and then formed strong, direct chemical bonds with iron atoms. Even neutral sugars attached themselves through hydrogen bonding.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/us-giant-robot-fights-wildfires/

This means ferrihydrite does not trap carbon using electrostatic attraction alone. It employs a multi-pronged strategy involving chemical bonds and hydrogen bonding to form strong, durable links. “Our work illustrates… that it is the sum of both negative and positive charges… that gives the mineral its overall positive charge,” Aristilde stated, clarifying the fundamental mechanism. This versatility turns iron oxides into “highly versatile carbon snatchers,” capable of securing many different types of organic molecules.

The implications are profound for understanding the global carbon cycle. “The fate of organic carbon in the environment is tightly linked to the global carbon cycle, including the transformation of organic matter to greenhouse gases,” said Professor Aristilde. By revealing the quantitative framework behind these mineral-organic associations, the research helps explain why some carbon remains protected in soils for centuries, while other compounds are more readily broken down by microbes and released as climate-warming greenhouse gases.

This discovery moves soil carbon storage from a black box into a clearer, chemistry-defined process. Next, Aristilde’s team plans to investigate what happens after molecules are attached—whether they transform into even more stable products or become available for degradation. This deeper knowledge could one day inform strategies for enhancing soil’s natural capacity to act as a long-term carbon vault, a critical tool in mitigating climate change.

READ ALSO:https://modernmechanics24.com/post/anduril-uk-project-nyx-partnerships/