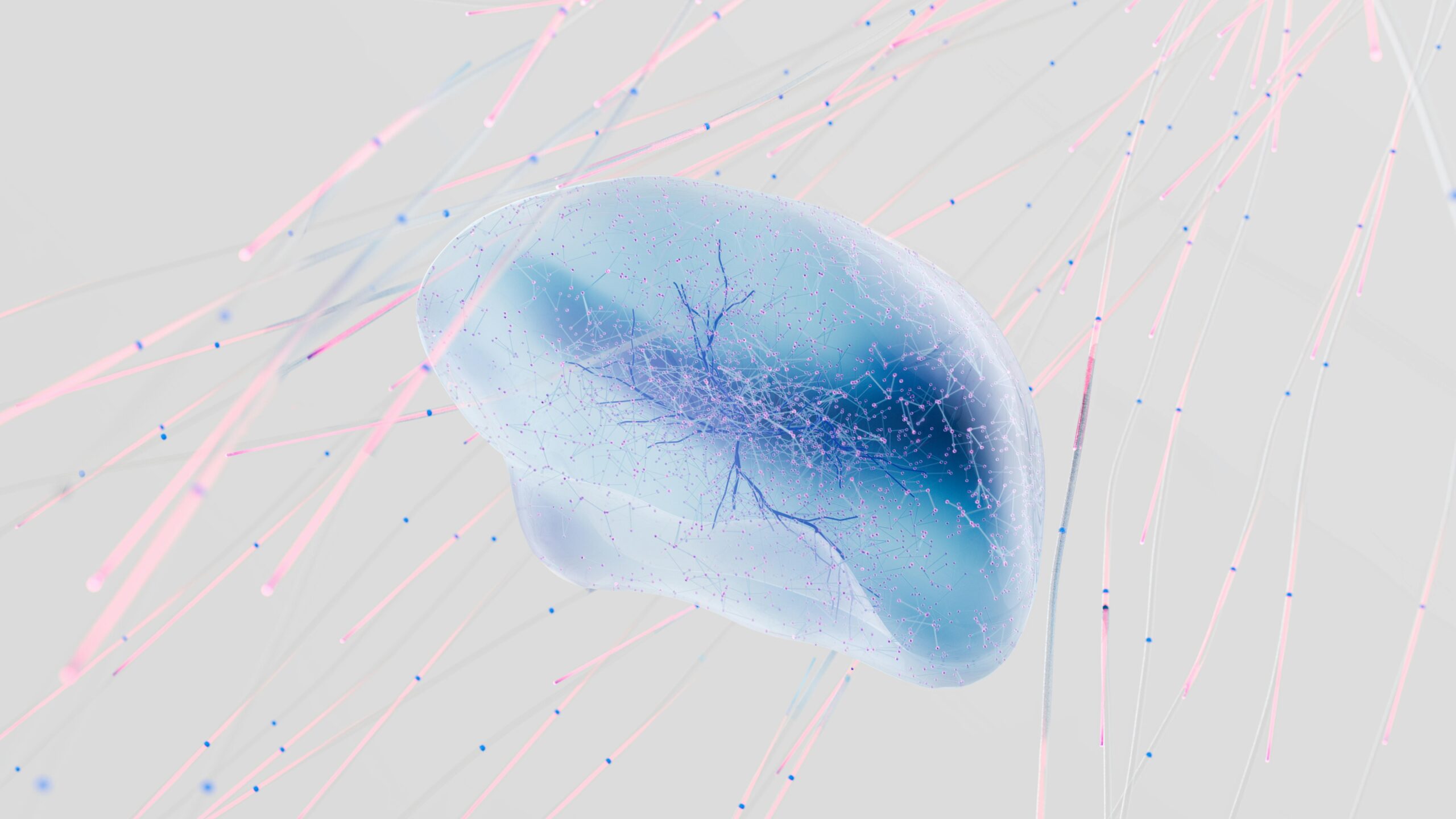

University of Hong Kong (HKU) researchers have created a new class of 3D, hydrogel-based semiconductors designed to integrate with the body like a “second skin,” potentially solving a major hurdle for brain-computer interfaces like Neuralink’s: immune system rejection. The soft, water-rich material aims to bridge the fundamental mismatch between rigid electronics and living tissue.

One of the biggest roadblocks to seamlessly merging the human brain with computers isn’t processing power or bandwidth—it’s biology. Our bodies are designed to attack and reject foreign invaders, and a rigid silicon chip embedded in soft brain tissue is the ultimate alien object. Now, a team from Hong Kong believes they’ve engineered a material breakthrough that could make bioelectronic implants truly biocompatible, paving the way for safer, longer-lasting neural interfaces.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/tum-startup-reinventing-rocket-pressure-tanks-2/

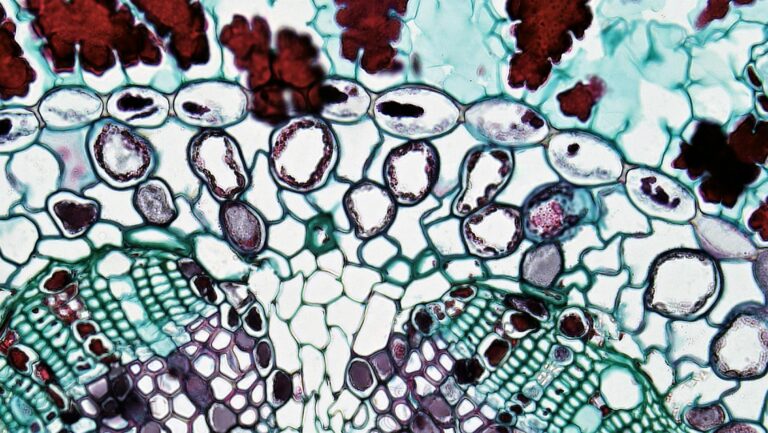

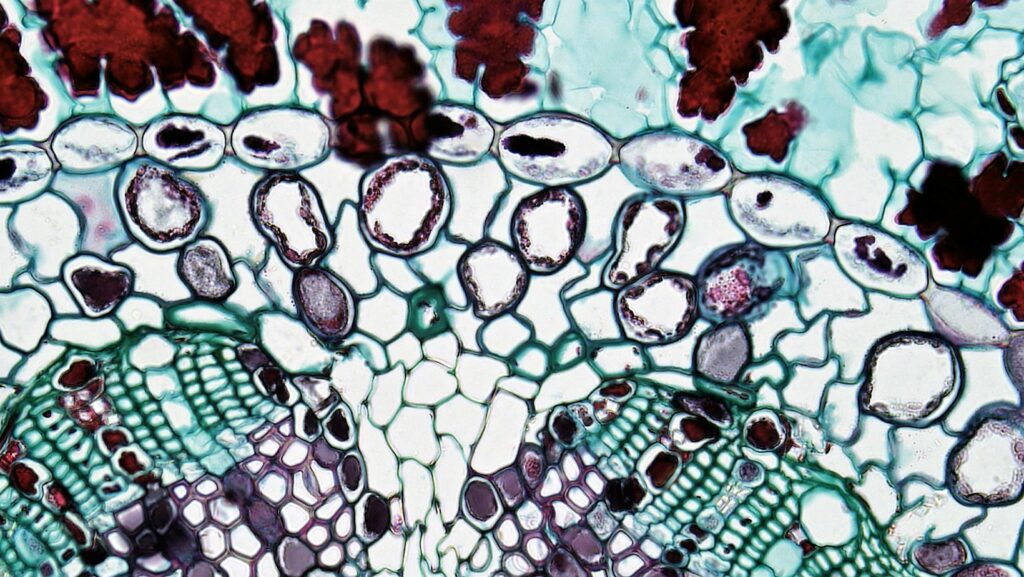

The breakthrough comes from a team led by Dr. Zhang Shiming, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong’s Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering. They have developed 3D semiconductors made from hydrogels—materials that are up to 99% water—moving beyond the inflexible silicon that has dominated electronics for decades. Their findings, published in the prestigious journal Science, could directly address a core challenge faced by companies like Elon Musk’s Neuralink, which is advancing invasive brain implants.

“Traditional semiconductors are made of 2D rigid, dry materials like silicon, which fundamentally mismatch with biological systems that are 3D, soft and wet,” explained Dr. Zhang. The new hydrogel-based semiconductors “address the material mismatch… which helps to suppress immune responses,” he stated, according to the South China Morning Post (SCMP).

The implications are vast for the field of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). Devices like Neuralink’s implant rely on electrodes inserted into the brain to read neural signals. However, the body’s immune response to these foreign objects can create scar tissue, degrading signal quality over time and risking long-term viability. HKU’s soft, wet electronics could act as a “second skin,” minimizing this rejection. “These biohybrid living transistors… have the potential to suppress immune responses, allowing for prolonged implantation while maintaining signal amplification capabilities,” Dr. Zhang said.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/us-supersonic-jet-cuts-flight-time-silences-sonic-boom/

The technology is currently at the fundamental research stage but has completed proof-of-concept lab work. Potential applications extend far beyond BCIs. The soft semiconductors could be used for deep brain stimulation to treat conditions like epilepsy, for creating prosthetic cardiac tissues to repair scarred hearts, or as a platform for developing energy-efficient neuromorphic computers that mimic the brain’s 3D architecture.

Dr. Zhang envisions a future where these materials enable a transition “from 2D, rigid and loose brain-machine interfaces to 3D, soft and robust interfaces for more accurate brain signal recording.” This could accelerate neuroscience research and lead to more effective treatments for neurodegenerative diseases.

Since the Science paper was published, the team has been contacted by numerous medical researchers eager to explore the platform’s potential. While a timeline for clinical use remains uncertain, the discovery represents a foundational shift in materials science for bioelectronics. It reframes the problem from one of miniaturizing existing electronics to one of reinventing electronics in the image of biology itself.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/sea-cows-engineered-the-arabian-gulfs-seagrass-ecosystems/

For companies like Neuralink, whose ambitions hinge on creating a stable, long-term human-machine link, such a material breakthrough could be the key that unlocks the next generation of implants. By making electronics as soft and wet as the brain itself, the University of Hong Kong team may have found a way to finally make peace between silicon and synapses.