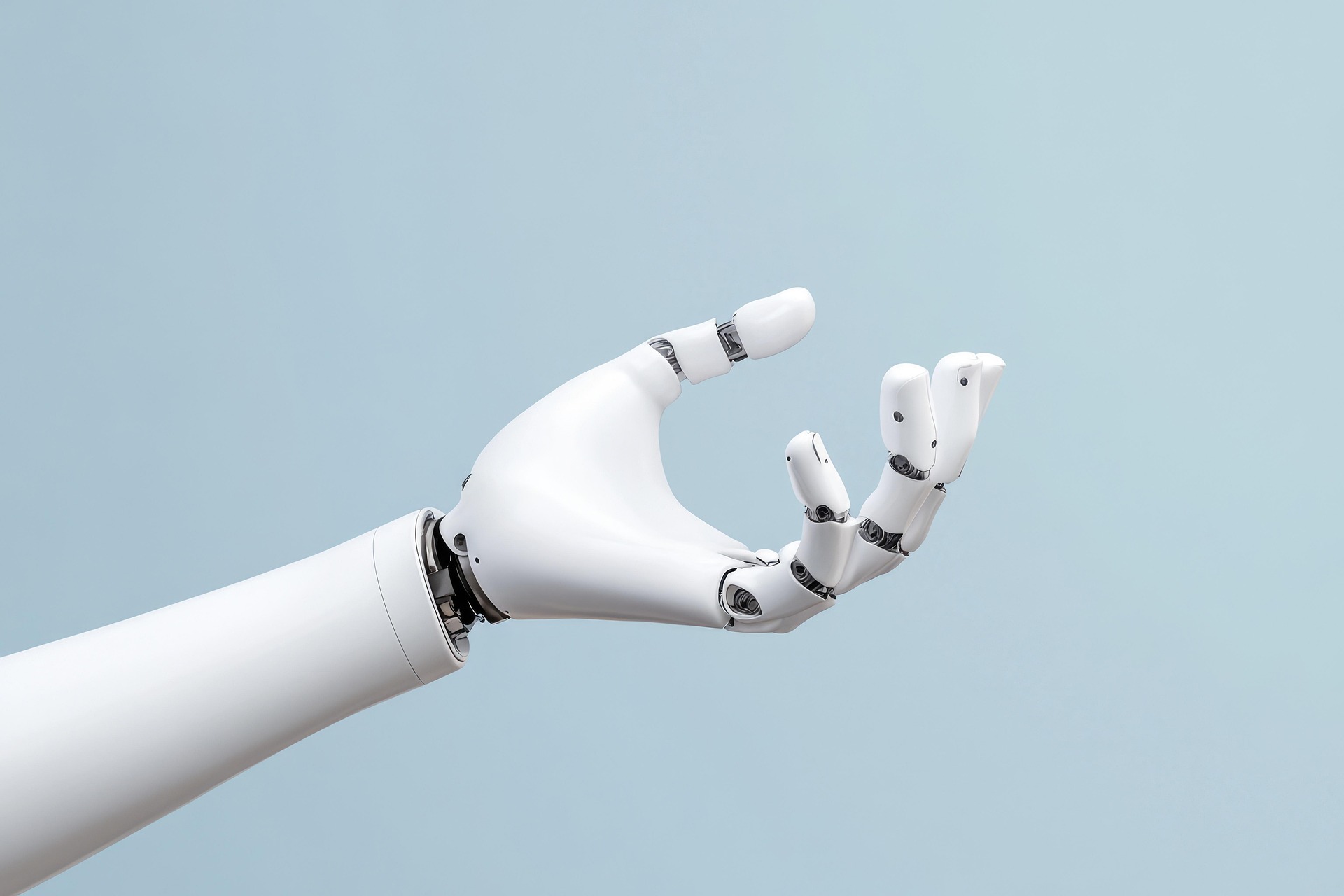

Engineers at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) have created a fully symmetrical, five-fingered robot hand that can detach from its arm, crawl spider-like across a table, and manipulate multiple objects at once. As detailed in their paper in Nature Communications, the design deliberately breaks from human anatomy to achieve greater efficiency, capable of 33 different human grasps while carrying a combined load of around five pounds.

In a scene straight out of a sci-fi thriller, a robotic hand unscrews itself from its wrist, tips onto its fingers, and scuttles away to complete a task. This isn’t movie magic—it’s a real innovation from Swiss labs. Researchers have built a dexterous robot hand that isn’t tethered by the same evolutionary constraints as our own, allowing it to perform feats like holding a tomato with two fingers while simultaneously securing a banana on its backside with another. “Evolution is a slow process… It does not explore all that could be possible,” the team writes, challenging the very blueprint of biological design.

The hand’s most startling feature is its intentional, perfect symmetry. It has five flexible fingers and what can be considered dual thumbs, allowing it to move with equal dexterity forwards and backwards. This means its palm and the back of its hand are functionally identical. In a demonstration video highlighted in their Nature Communications report, the hand, while attached to its arm, picks up a mustard bottle, flips over, and grabs a bag of chips with the opposite side. This fully symmetrical design is the key to its multi-object manipulation, a task that would baffle any human hand.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/navy-admiral-modular-frigate-construction/

But why design something so… unsettling? The researchers argue that our own hands, for all their grace, are limited by their asymmetrical shape, single opposable thumb, and fixed attachment to the arm. By freeing themselves from these biological constraints, they could optimize purely for function. They took inspiration from nature, just not from humans. The team points to octopuses and certain insects that use their limbs for both locomotion and manipulation. An octopus’s arm can twist a jar lid open while another explores its surroundings—a model of decentralized, multi-purpose control.

The practical mechanics are as clever as the concept. To design it, the team created a digital library of human grasps and used an algorithm to solve for the optimal number of fingers and range of motion needed for both manipulation and crawling. They discovered an engineering sweet spot: while increasing from three to five fingers improved crawling efficiency, adding more led to diminishing returns due to added mass and collision risk. The result is a hand that can detach, crawl to a target using its fingers, and perform complex carrying tasks independently.

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/south-korea-showcases-multi-purpose-military-ugv/

This philosophy stands in stark contrast to the major trend in robotics, where companies like Tesla and Figure are investing heavily in humanoid designs that mimic our own form. The Swiss approach asks: why be bound by human shape at all? As reported in their study, this design could lead to hybrid systems where a humanoid robot uses a standard arm for most tasks but deploys this detachable “hand crawler” as a tool to retrieve items from tight or hazardous spaces, effectively acting as a multi-functional, mobile end-effector.

While its immediate application might be in specialized logistics or factory maintenance, the team’s work fundamentally expands the vocabulary of robotic design. It proves that efficiency doesn’t have to look familiar, and that the most capable tool might just be one that can walk—or crawl—away on its own.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/us-navy-plan-to-fight-warship-rust/