Scientists at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) have confirmed that the primordial “quark soup” created in atomic smash-ups expands outward like a single, cohesive fluid. The new analysis from the ATLAS Collaboration, led by physicists from Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook University, measures for the first time how this radial expansion is driven by the sheer size of the explosive fireball, offering a fresh tool to probe the fundamental viscosity of the early universe’s perfect liquid.

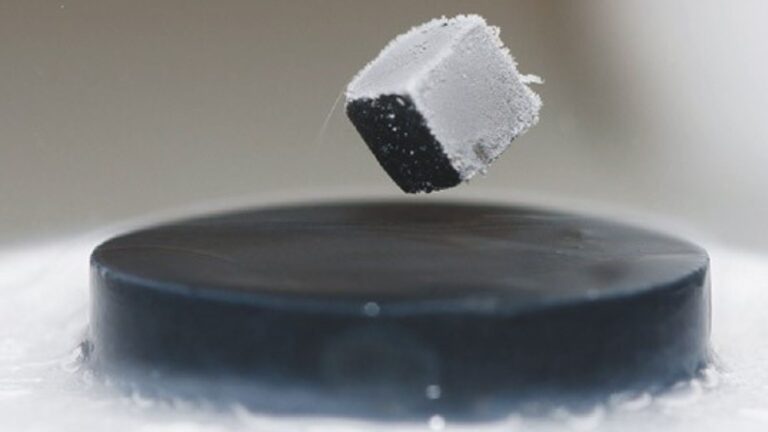

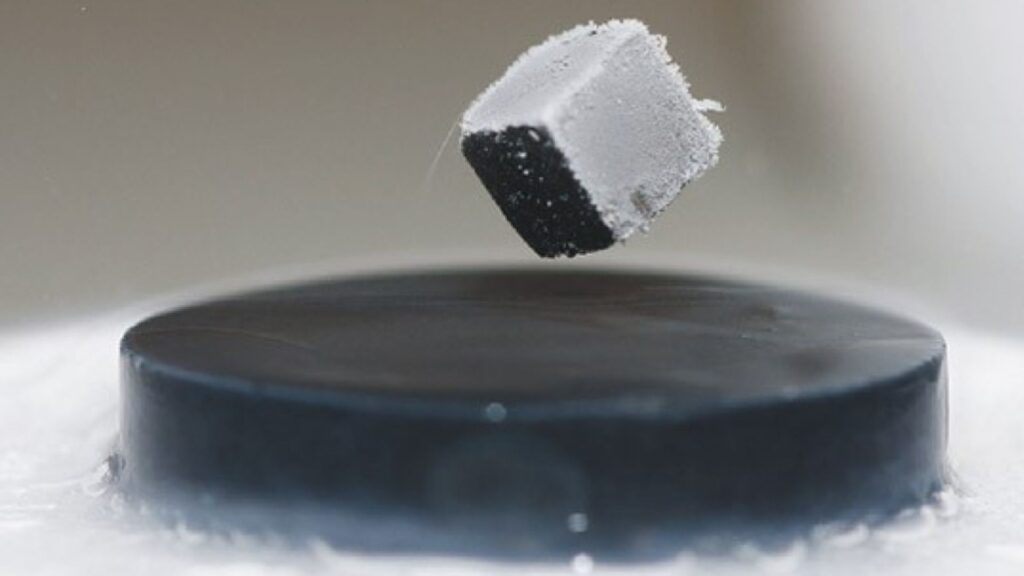

What happens when you strip atoms to their cores and smash them together at nearly the speed of light? You recreate conditions not seen since the first microseconds after the Big Bang, forging a searing hot state of matter called a quark-gluon plasma (QGP). For over two decades, scientists have known this plasma flows like a nearly frictionless liquid. But most evidence came from studying its shape—specifically, an elliptical flow pattern. Now, as reported in Physical Review Letters, researchers have precisely measured its radial flow—the uniform, outward push in all directions—and confirmed it is a true collective behavior of the entire system.

“Earlier measurements revealing that particles flow collectively from heavy ion collisions were central to the discovery of the quark-gluon plasma,” said Dr. Jiangyong Jia, a physicist at Stony Brook University and Brookhaven National Laboratory who led the new ATLAS analysis. He explained to Brookhaven Lab’s press office that while elliptic flow revealed the QGP’s response to the collision’s shape, radial flow is sensitive to the overall pressure generated by the fireball’s size. This distinction is crucial because it gives scientists a new way to measure a different property of the plasma: its bulk viscosity, or resistance to expansion.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/navy-bets-big-on-containerized-missiles/

The experiment involved colliding beams of lead ions in CERN’s 17-mile-long LHC ring. The team, including graduate researcher Somadutta Bhatta, then sifted through data from the ATLAS detector to analyze the momentum of particles streaming out transversely from millions of collision events. Their goal was to find a specific correlation predicted by theorists: in collisions that produce the same number of particles, a smaller, denser fireball should have stronger internal pressure, leading to a more powerful radial push. “It’s like if you put the same amount of water into two different sized balloons and poked a hole in each; the water is going to come out faster from the smaller balloon because it’s under higher pressure,” Bhatta illustrated.

The data confirmed this elegantly simple relationship. In events where the collision overlap region was smaller, more high-momentum particles were produced. When the QGP blob was larger and more diffuse, the radial push was weaker, yielding more low-momentum particles. According to the Brookhaven Lab report, this pattern held true at all angles, proving the expansion is a global phenomenon of the entire droplet of QGP, not just a localized effect. “Our results confirm that radial flow, like elliptic flow, is truly a global collective phenomenon,” Bhatta stated. “The outward radial push is carried by all the particles.”

WATCH ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/us-giant-robot-fights-wildfires/

This finding completes a picture that began at Brookhaven’s own Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), which first discovered the perfect liquid QGP in 2005. “In some ways, these radial flow measurements are completing a story that started the minute RHIC turned on,” said Dr. Peter Steinberg, a Brookhaven physicist and co-author on the paper. The new analysis provides a pathway to answer lingering questions, especially about the plasma’s compressibility. Since radial expansion can be slowed by bulk viscosity, measuring this flow allows physicists to test just how “squishy” the quark-gluon plasma is—a key property for understanding the strong force that binds the universe’s core components.

Perhaps most importantly, this method isn’t reliant on the collision’s shape. This makes it uniquely powerful for studying the tiniest possible droplets of QGP, created in collisions of small nuclei like protons, where defining a shape is notoriously difficult. The synergy between facilities like RHIC and the LHC, and between theorists and experimentalists, continues to peel back layers of this exotic state of matter. As Jia noted, these powerful tools are complementary, allowing science to move forward by viewing the same profound physics across different energies.

READ ALSO: https://modernmechanics24.com/post/robot-coffee-cup-self-driving-trivet-ai/